When you’re a 9-year-old boy, where things fit in the world seems very important. I know this because at any one time, my 9-year-old son Jack can tell you where he fits amongst his friends and classmates. Who’s older and who’s younger (very important). Who’s taller than him and who’s shorter (also very important). Who’s a faster runner and who is slower (you get the idea).

Comparison is how Jack sees the world at the moment. What’s better, what’s worse? He could tell you his favourite chocolate bar, and his second favourite soft drink or tree. Jack, dear reader, could tell you his third favourite colour. He also has a long list of favourite songs and can give you information on how those have been carefully stratified. Within that, there will, I am sure, be a specific sub-list for songs by his favourite artists. He can tell you, quite specifically, what he likes about playing football and how that tracks against what he likes about playing rugby. He has clear views on whether that superhero would beat that superhero in a fight.

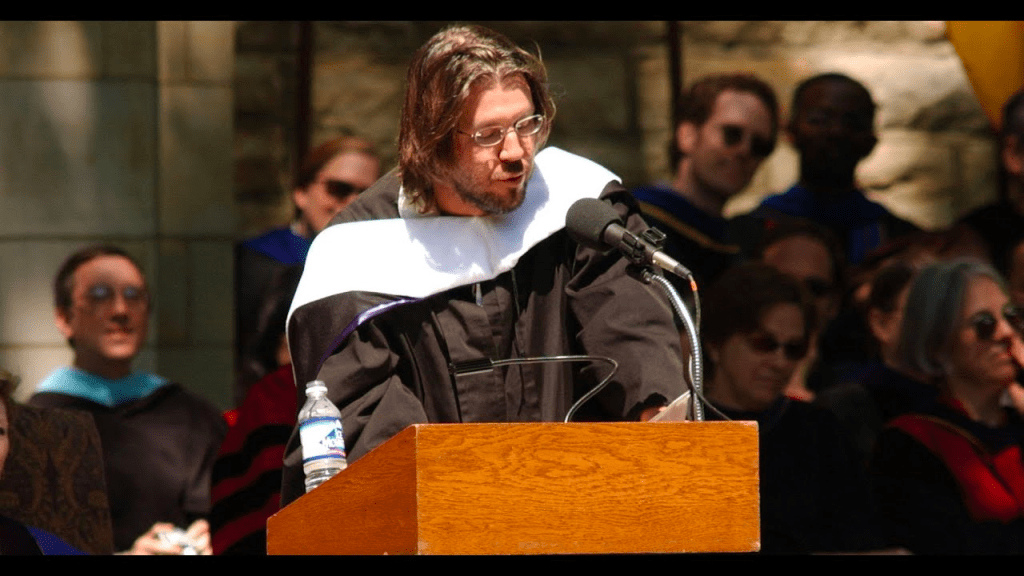

Because that’s the way Jack thinks, he thinks other people think that way too. As the brilliant and heartbreakingly short-lived American writer, David Foster Wallace once noted (with irony, of course):

“Everything in my own immediate experience supports my deep belief that I am the absolute centre of the universe; the realist, most vivid and important person in existence.”

David Foster Wallace

So it’s not surprising that a 9-year-old thinks that everyone thinks like him, because his only experience of thinking is the thinking he does, right?

The result is that you don’t have to spend much time at all with Jack before he’s asking you what your favourite something is. He expects you to have a favourite, and he will push you if you say you don’t. I now have a third favourite colour, because it’s easier than not having one.

On the whole, I go along with Jack’s world of categorisation because it’s interesting to question your own view of the world in a way that you usually don’t. Hang on a minute… what is my third favourite colour??*

The other morning as we drove through the hedgerow-lined country lanes between our house and Jack’s school, which sits in the village perched on top of a hill on the other side of the valley [yeah it does sound pretty idyllic, doesn’t it?] we chatted about his tendency to rank things and why he did it. After a couple of failed attempts to get some insight (“I like it because it’s good to know what you like the best”), I hit a breakthrough…

“I like asking myself questions. It makes me think about what I think about things.”

Woah. Pretty deep for the school run, right?

So once I’d managed the massive hit of dopamine that paternal pride dropped into my system which made we want to hug him and burst into tears and shout his name from the top of the church tower in the distance all at the same time, I gathered myself and told him I was proud of him and that asking himself questions was really important and he should never, ever stop.

Then, once I’d dropped him off at the drive-through turning bit [he doesn’t need me to come into the playground any more because he’s Year 4… I also haven’t got a hug from him at school for quite some time, but we do have a “Bartlett Boys Fist Bump™” – my little man is growing up too fast] I found myself thinking about what he’d said.

He doesn’t know this, but what he’s doing is called ‘meta-cognition’: the process of thinking about one’s own thinking. It’s what David Foster Wallace was talking about, and taken to the next level you get to meta-emotion which is considering how you feel about your feelings. Being able to take a step back and consider your thoughts and feelings with objectivity and ‘detachment’ is actually the fundamental idea of Buddhism, and much of meditative teaching: you are not your thoughts; you are not your feelings.

I’m not saying Jack is on the road to enlightenment just yet – he’s much too ‘attached’ to the idea of getting the football into the top corner of his little goal in the garden, for a start – but I’m not sure I was thinking about my thinking at his age.

But the point of all this stuff is not just to get you thinking about what you think, or even exploring how you feel about your feelings. It’s to tell you about what this desire to question and categorise has led young Jack, and where I’ve gone with him on the journey.

Ladies and gentlemen and all those who identify as they wish, I give you:

The Power of IF

Allow me to explain. A little while back Jack came to me and asked who I thought would win in a match between his beloved Liverpool Football Club [YNWA] and England. At the time there were a couple of Liverpool players who would be in the England team, and so I told him that wasn’t possible – who would they play for? To which Jack replied…

“Yes but what IF they played each other”

For Jack, IF is the get-out clause – the escape from the realm of reality into a place where anything is possible. Because whilst you can know that in reality, it wouldn’t be possible for a team to play another team with some of the same players on each side, there remains the question of IF they did, who would win?

I know a grizzly bear won’t ever fight a tiger in the wild, but IF they did, who would win?

I love the freedom of that thinking. It’s the stuff we leave behind when we become adults and become constrained by the things we know to be true, rather than exhilarated by the potential of those things that could never actually be, but what if they could?

And it’s that additional word, turning IF into WHAT IF that has become something of a guiding principle for me over the last year or so since “my little episode”. WHAT IF? is a commitment to the possible. And the magic of this little phrase is that the positive always, without exception, has the ability to trump the negative.

What if it doesn’t work?

Yeah, but what if it does??

What if we could create this amazing thing that feels impossible? Wouldn’t that be cool? Well shall we try to actually do it then? Rather than dwelling on all the reasons why it’ll be too difficult?

What if you could get past the difficult conversation that you’re worried about starting because you don’t get to choose how the other person takes it? What if it works out? That would be pretty great, right? So go and work out how you’re going to at least try to do it.

What if you say “I love you” first and they say “I love you too”? Yeah, I get it’s one of the most vulnerable things possible, and yeah, what if they don’t? But what if they do??

It’s become such a positive influence in my life that I’ve done what I tend to do in this situation and had it tattooed onto my arm, so that whenever things get stuck I can envisage the positive endpoint and make a commitment to go for that.

And that, dear reader, is what I’m going to ask of you today. No, not the tattoo. You don’t have to do that if you’re not up for it. No, I’m asking for a commitment, just with yourself, that the next time someone uses ‘what if’ negatively you flip it to the positive and embrace the possibility of a positive outcome, and commit to go towards that.

So yeah, what if we lose? What if they hate it? What if they say no?

I get that you’re nervous. It’s a big deal. But we’ve done all we can. And what if we win?

Yes, there’s a risk of that. They may hate it. But what if they absolutely love it?

And just imagine, for a second. Let yourself go, and give a little thought to this…

What if they say yes?

Good luck. And let me know how it goes.

*[I thought about this only this morning for the first time. My favourite colour is yellow – always has been. Bright, positive, unmistakable. Next (because I had to choose) comes blue, because of the sea and the sky and calmness and all that. And I thought my third was green, but when I told Jack he said “Oh, I thought it would be orange”. And actually, I think he’s right. So it turns out that not only does Jack know his own third favourite colour (turquoise, surprisingly), but he also has a better idea about mine. He can probably help you with yours, too.]